Techniques and practice…

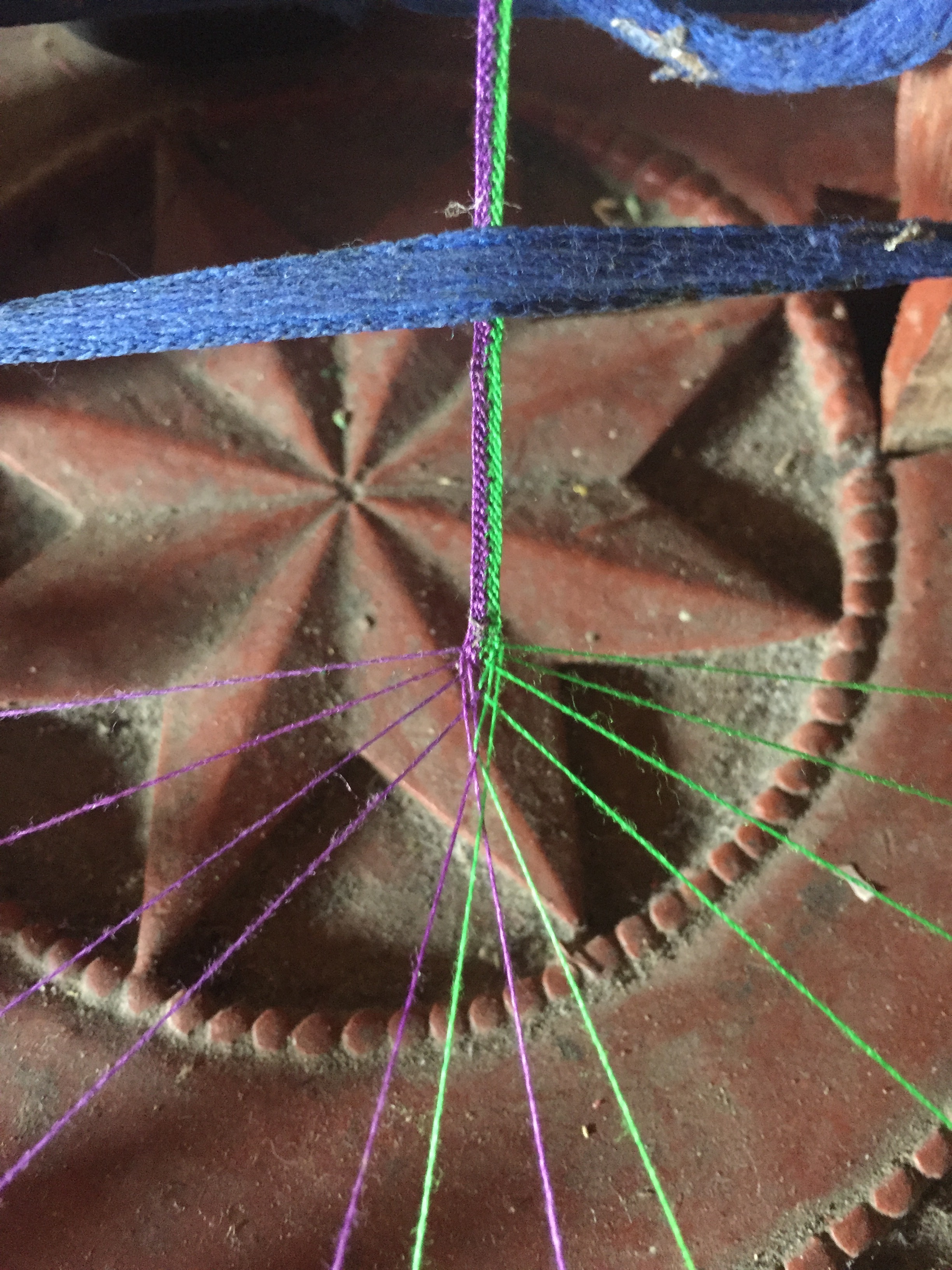

A variety of textile traditions are still practiced by hand in Dali. Some of these traditions are slowly dying out and some have already dissapeared from the community altogether. Among the women living in Dali today you can step back each generation and find a wider and wider body of knowledge and techniques that are still known. The oldest women are still adept at growing and spinning cotton into thread — whereas the next generation down tends to purchase it today. Approaching some of the great-grandmothers in the village usually results in the sharing of a surprise trove of lesser-known techniques such as narrow hand woven belts showing a variety of patterns, small quilted pieces, or intricately wrought trims to embellish clothes. Above is a heavily ornamented hand-carved stool whose sole purpose is the production of a very narrow braided trim that is used on women’s shirts. To make this trim one sits in front of the stool gathering up each weighted thread between the fingers and proceeds to braid two colors together creating a spool of this trim. The trim is then carefully hand-sewn onto shirts giving them a distinctive piped edge that contrasts with the dark indigo of the base cloth. What makes this trim interesting is that in within the prescribed order of traditional forms of making this is the space to express individuality — by choosing the two colors to use in the trim. Ultimately all the choices of trim color and embroidery decisions add up and make one’s sartorial ensemble look distinctive and individual, yet also unified with patterns and forms of the group at a macro-level. In this sense, the rules of creativity within tradition are both a means of expressing one’s voice and personality while balancing with the need to strengthen the identity of the whole.

Hand weaving cotton…

Many women still hand weave cloth in Dali. There are generally two types of cloth that are still made, one is plain woven natural fabric that is then later dyed with indigo and the other is an indigo and white striped fabric that was typically used for making bedding and items of daily use. The striped cloth is still made but is not turned into bedding as inexpensive factory-made blankets and sheets are now typically purchased. Before the striped cloth is woven the thread is dyed in indigo and hung out to dry on long wooden poles outside the home. The Dali project has aimed to find new uses for this striped cloth that express both its handwoven beauty, with subtle differences in the stripes from each weaver, and its more daily, pragmatic sensibility.

There is a local saying that ‘Dong cloth is a way of life’ — this can be understood though the idea that it takes at least two people to thread a loom—therefore if for example, a mother and daughter-in-law have a fight they will have to quickly repair their feelings in order to collaborate the next day on the treading of the loom. In other words, there is embodied within these textiles a fundamental concept of continual repair and weaving the social cloth. These practices represent not only a way to show individual skill and expression but also are a way of being—that is, being together.

In Dali the looms are quite narrow, which results in a cloth that is typically 30-40cm wide. This limit results in the distinctive patterns clothing and and forms other items take in the village — but is a significant limit when applied to the demands of contemporary parameters for fashion or other products. Weavers in other areas of Guizhou have experimented with building wider looms and it is small innovations like that that help to bridge between tradition and current need.

Only a handful of women still grow cotton themselves in Dail and spin it into thread. Most thread is purchased outside the village. With today’s demands for organic certifications and need for transparency and documentation across the entire supply chain the dissapearance of this practice in the village cedes some of the autonomy and control regarding the integrity of the entire production process. On the other hand, adding this labor intensive step to the weaving process will further raise the cost of the cloth and may hasten the demise of hand-weaving as a whole. Tradition as such is not a fixed concept — and decisions about production need to reflect a balance between competing needs.

Gathering cotton high up in the fields.

Local proximity of materials is important for the final visual result and quality of the craft process. Cotton grown locally is optimal for use with local indigo dye and attempts at using cotton from climatically different places such as Xinjiang have been tested in the past where it was found that the essential alchemy between cotton and dye did not work well. Even within the same region there can be substantial differences — located high in the valley of a mountain crest, surrounded by forest, Dali is not only a few degrees cooler than the township located a thirty minute drive away but is known to produce indigo plants of a better quality and a special yield of blue.

Indigo Dye…

Dying fabric indigo blue is a multi-stage process that takes a nuanced understanding and long experience with the plant material. There are multiple varietals of indigo plant grown in Guizhou, with some that grow better in shade and cool temperatures and others in the direct sun. This diversity allows the hyper-localization of indigo dying practices across a region with a range of varying micro-climatic conditions. When it is picked and the stems of the green indigo leaves bleed, the sap actually turns blue on contact with the air. Two Japanese anthropologists, Sadae Torimaru and Tomoko Torimaru, exhaustively documented indigo dying practices during their almost twenty years of field work in Guizhou. Their text, Imprints on Cloth, has helped to decode and better understand the chemistry of the dye practices in Dali.

The first step in the dye process is extracting the pigment from the indigo leaves to make indigo paste. The leaves are packed into a plastic or wooden tub and covered with water. Over just a few days the leaves begin to release their blue and then ferment. Once they have fermented the leaves are pulled out, leaving behind a bluish water. The water is then aerated over and over again by pouring it from high above the container and therefore exposing it to air to oxidize the pigment. After a time a glossy blue foam appears on the top of the vat. This is left to settle for a number of days while the pigment sinks to the bottom where it can be gathered up and separated from the water.

Once the indigo mud is extracted it is the basis for creating the dye bath. The recipes and formulas for making the dye bath vary by place and are dependent on factors such as the type of indigo being used. This stage is very delicate because getting the indigo mother dye to take to the bath and turn into an active dye can be somewhat tenuous. The days chosen for doing this must be auspiciously chosen on the monthly calendar and it is very important that the person starting the bath be the correct person, for example a women who is pregnant is believed to be detrimental to getting the dye to take. Rice wine is the primary solvent for the pigment and depending on context other natural elements are added such as lye made from wood ash. It takes around two weeks with occasional string and adjustment to get the dye to take. No synthetic chemicals are used and the process results in a cold-dye bath that can be maintained and kept “alive” for up to a year.

Torimaru, Sadae, and Tomoko Torimaru. Imprints on Cloth: 18 Years of Field Research among the Miao People of Guizhou, China. Nishinippon Shinbun, 2010.

Some women in Dali are experts at embroidery, others at sewing, many still weave — but some do not, but almost without exception all the houses have a dye bath. It lives either just inside the kitchen or just outside the kitchen door so it can be easily watched, tended, and periodically used for adding another coat of blue to the fabric in the process of being dyed. Cloth is not dyed merely out of need but is a fundamental expression of identity and belonging to the Dong cultural community. Houses often have the blue cloth draped from their balconies as women are continually in the process of practicing this tradition alongside their other daily work.

Making Glossy Cloth…

Perhaps the most striking textile in Dong and Miao traditions is glossy cloth. It iridescent purple sheen and often leathery feel place it outside immediate understanding and categorization of known types of cloth. It is stiff and formal and inherently leads to more ceremonial types of patterning and clothing uses. When shaped into items of clothing it allows for a kind of shadowed and transforming elegance to form as it holds its own emptiness and space around the body.

One roll of glossy cloth can take many years to make and each village and community has their own particular way of making it. The handwoven cotton cloth is dyed to a deep indigo many times over the course of a year or even two. The cloth can then be over dyed with a with red from botanical materials or pig’s blood to take on a deeper, more purplish hue. Lastly it is soaked solutions based of water buffalo fat or egg whites to coat the fibers or it is left plain. This is then followed by multiple intensive rounds of pounding or polishing of the fabric roll in order to stiffen and develop gloss.

Calendaring the cloth to achieve high gloss and stiffness

Cloth will be calendared multiple times over the course of a year or even two years