Textile traditions in Dali 大利 village…

A focus on textile traditions is to focus on the lives of the women in Dali village. Many women in Dali still practice hand-weaving, embroidery, and many more still, indigo dying. These skills are core to their sociocultural identity in this place. The textiles are typically not made for sale but are instead made as individual expressions of aesthetics and skill to be used by oneself or gifted within one’s family. A sense of camaraderie and competition exists amongst the women as they the results of their labor with one another. Today though fewer and fewer women of the younger generation have time or interest in learning these traditions—especially as they travel and live outside the village for work. The result is that the knowledge of these skills is failing to be passed from one generation to another and now stands at an impasse. Additionally, women who have stayed behind to live in the village have very limited means of accessing capital and therefore have less bargaining power in the highly gendered social context. Therefore it is when these textile practices start to take on a commercial dimension and represent a means of earning profit they begin shift in relevance and importance in the eyes of the entire village.

Therefore building a social enterprise and generating income is a primary goal of the project, and yet it is equally critical to examine the continued value of the social, ritual, and artistic aspects of these practices. Textile production does not stand in isolation as an impressive set of skills and techniques — it is at its core an important element in producing the social bonds that make Dali a resilient social whole with a strong 侗族 Dong identity. With this in mind, the project aims to develop means to support multiple aspects of the material culture of textile production in the village. Central to this mission is the formation of a textiles cooperative in Dali that allows the women to better leverage their skills economically as well as create the conditions for the preservation and evolution of this textile knowledge.

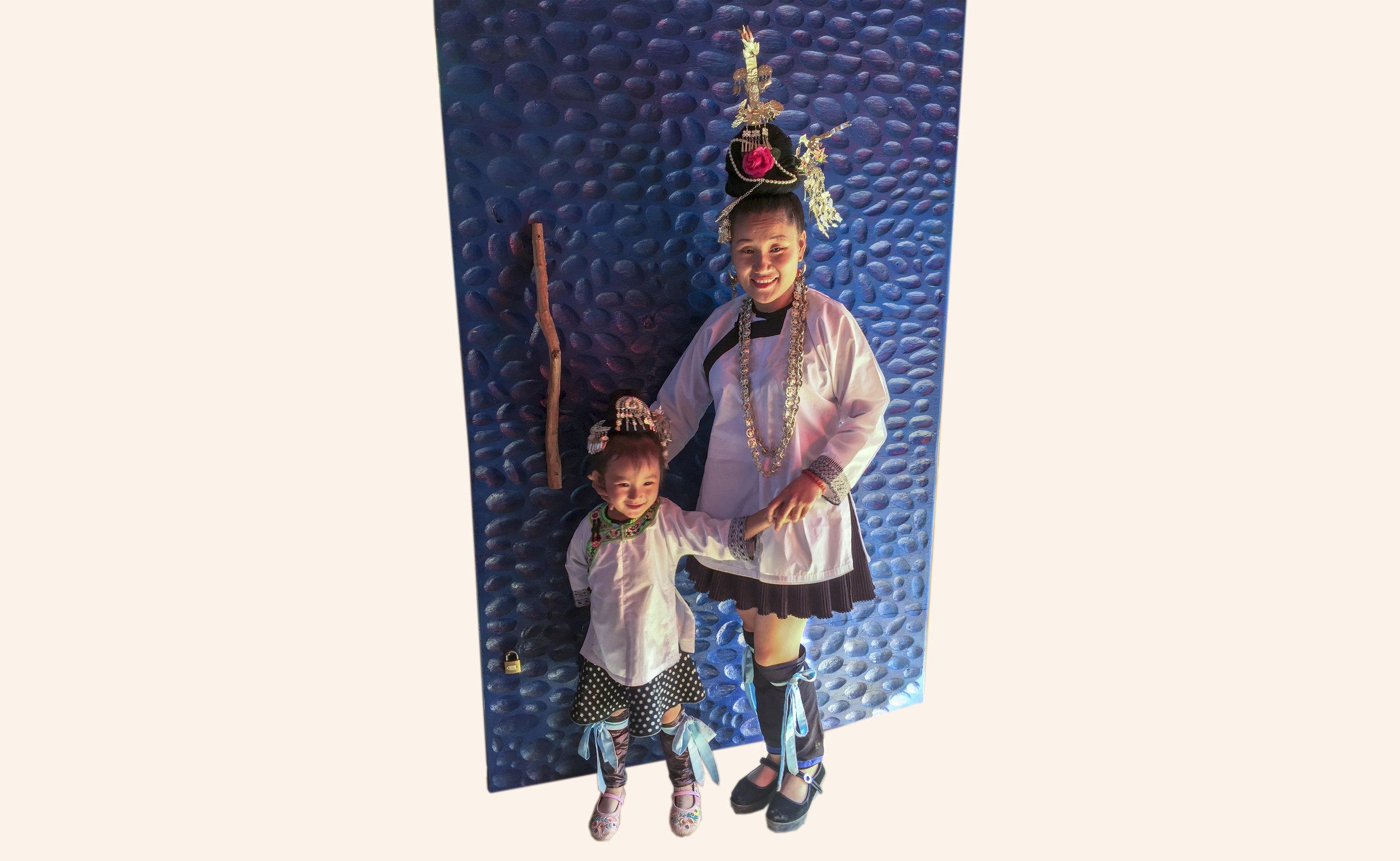

A key part of the project is documenting the existing textiles owned and used by various families in Dali. Ranging from very old pieces passed down through generations to pieces in the process of production now — one can see the broad range of authorship and creative energy that creates the textile culture. The above images are just a small sample of the variety of items owned in the village. Clothing ranges from the everyday to ceremonial pieces both for women and for men. These items are worn today with a mix of “outside” clothes but are still critical signifiers of identity and pride. Blue and white embroidered headscarves are not often worn but are still occasionally made as a way to demonstrate skill and expression through needle-point. The patterns and motifs are significant not only in what they represent but as a structural geometric order that bound and guide the spatial / structural dimensions of the cloth. In this way it is important to keep these historical pieces within families so that future generations can use them as templates to learn from and as visual references to inform their own work. Perhaps one of the most important pieces of textile production that is currently still widely practiced is the making of baby carriers. A baby carrier is a way to almost ritualistically prepare for the next generation through the act of creation, and these pieces combine a variety of techniques (embroidery, dye, applique, etc…) that can be produced at different points in time and will eventually come together as a bricolage to make the carrier. The baby carriers are passed down through generations, therefore creating a line of continuity that shows care and effort for those who are here and for those who have have not yet arrived.